Engineering culture never stands still. Yet, one challenge remains as relevant as ever – the sense of responsibility that engineers bring to their work. Or don’t.

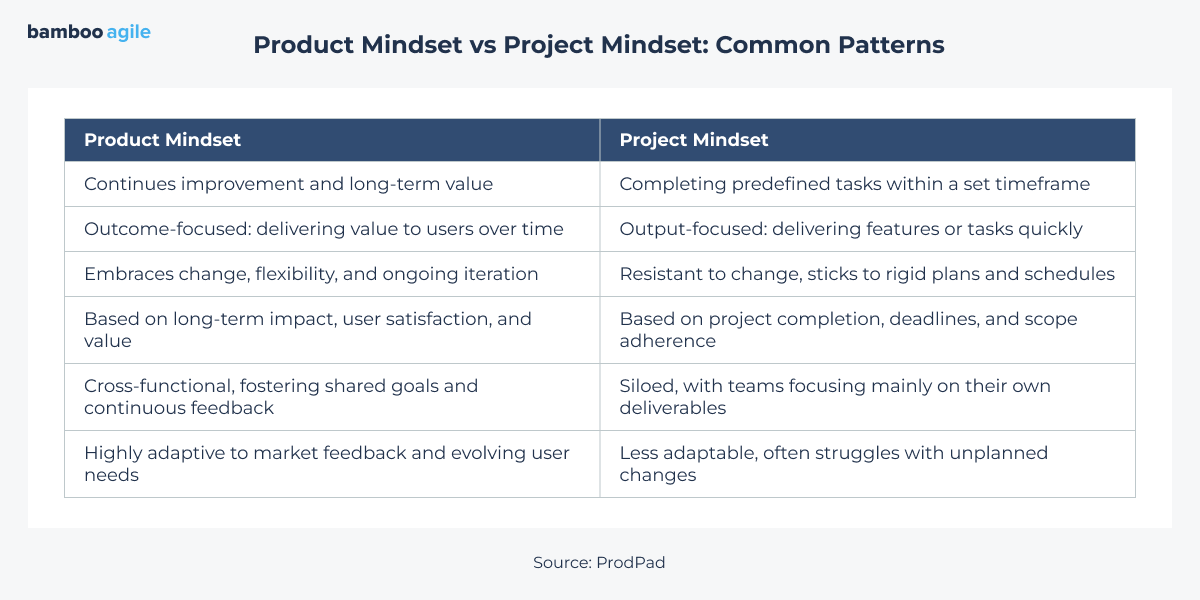

This very mindset – going beyond just closing tickets – determines whether a product becomes fragile and weighed down by tech debt, or delivers real value to users. Many in the industry see it as the defining mark of quality software development today.

So how can companies create and sustain such a culture? And what helps motivate developers to take responsibility not only for their code, but for its real-world impact?

We’ll explore these questions together with our colleagues – Maxim Leykin, Head of Engineering; Alexey Shinkarev, Engineering Manager; and Vasilij Ninko, Engineering Manager at Bamboo Agile.

Meet the Bamboo Agile engineering leaders

Maxim Leykin

Maxim began his IT career in 2004 as a C++ developer, later transitioning to Java and Android development. He has worked on over 15 mobile projects of various scales, taking on roles from software engineer to team lead and project manager.

Since 2015, Maxim has been focused on engineering and managing the delivery of mobile and cross-platform solutions in the IoT, automotive, and fintech domains.

At Bamboo Agile, he is responsible for implementing the company’s technology strategy, strengthening technical expertise, evaluating and developing new projects, and consulting on complex engineering challenges.

Outside of work, Maxim frequently speaks at tech conferences and lectures on Java and Android development at universities.

Alexey Shinkarev

An engineering manager with 17 years in software development and a focus on web applications (JavaScript/TypeScript, Node.js). A hands-on backend developer.

At Bamboo Agile, Alexey has established development processes from the ground up for a wide range of projects – from internal R&D initiatives to client products with tight deadlines and budgets worldwide. He has led cross-functional teams of up to 15 people, including engineers, QA specialists, designers, and analysts. To date, Alexey has successfully onboarded 60% of Bamboo Agile’s current development team, many of whom have become the company’s top specialists.

Vasilij Ninko

Vasilij entered the tech industry 15 years ago as a full-stack PHP developer, working across banking, manufacturing, and service sectors. Later, he switched to Perl and then to JavaScript, moving from backend projects for mobile operators to e-commerce, HR, EdTech, and other domains.

Vasilij explored various roles before assuming the positions of Team Lead and Engineering Manager. Now, he focuses on building development processes, managing timelines, and guiding team growth and composition. Vasilij also serves as an active bridge between business and engineering.

What drives or limits ownership in engineering teams

So, many say developers often focus too narrowly on following the spec instead of seeing the bigger picture behind a feature. Where do you think the root cause lies? Is it missing access to full product context, a lack of breadth and critical thinking, or a reluctance to take ownership?

Vasilij: The reasons can vary. Some developers deliberately choose not to know – or not to want to know – the product context. For them, the task itself is mostly interesting as a technical challenge.

Another typical case is the objective lack of real access to user feedback. For example, when a product manager doesn’t collect it properly and instead relies on personal preferences. Similar distortions in understanding what users actually need can also happen when the product is driven more by C-level vision than by real feedback.

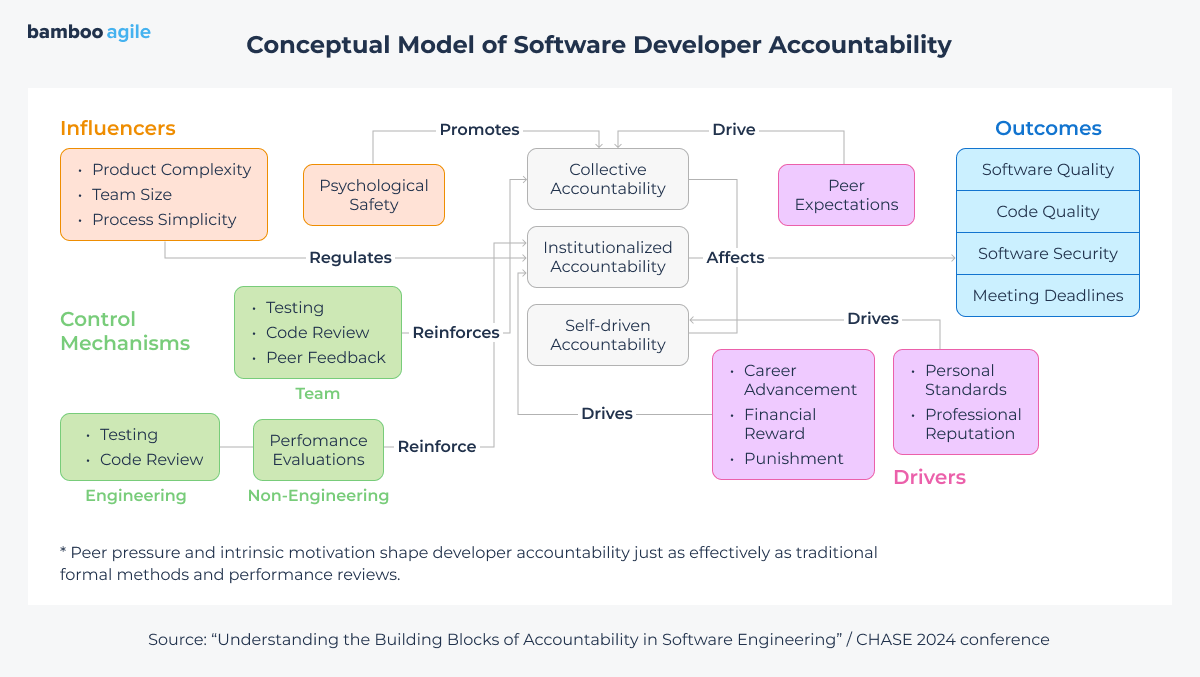

Alexey: And still, the reluctance to take responsibility for seeing a feature through to the end happens more often than one would wish. Sometimes, no matter how much context you provide or how well you align on timelines, if someone doesn’t want to take ownership, nothing will work.

Maxim: I agree with my colleagues for the most part, but I’ll probably play a bit of an advocate for some developers [laughs]. It’s worth saying: teams are not monolithic – we’re talking about people with diverse skills, seniority, mindsets, and levels of responsibility. For junior and some mid-level developers, it’s probably normal to simply “close tickets,” as they may not be capable of optimizing something for the broader context. Moreover, attempts to do so without sufficient skills can even be harmful.

At the same time, some people simply don’t feel comfortable taking on too much responsibility – not because of a lack of skills, but because of their mindset. And that’s normal too.

The key point here is that if there’s initiative, it should be encouraged by management. And the context should be provided once the developer is ready for it.

Listen to the podcast episode with Maxim Leykin

On Agile Redemption, Maxim discusses how to grow a product engineering mindset in development teams, helping engineers take ownership and think beyond the code.

Alright, let’s get a bit practical. Can you recall a case where the team delivered exactly to plan, yet the product metrics barely moved? What went wrong, and what was done next?

Vasilij: Let me take this one. I’ve come across it more than once. For example, it often happens during quick experiments to see what will or won’t appeal to users.

One case that comes to mind from an e-Commerce project is when we added extended filters with multiple parameters.

Based on the metrics we collected, only about 10% of users were using product filters. But among those who did, the conversion rate was noticeably higher. So, we decided to add an extended filtering feature – assuming that people who already used filters would find what they needed more easily. And that those who hadn’t would start using them because they had been missing something before.

In reality, it turned out the opposite – even fewer people used the filters. So, we rolled it back and went with a different solution that actually worked: intelligent sorting in the product listings.

It turned out that all we needed to do was to show, for example, only the models that had a full-size range first. And that alone improved the sales funnel metrics. But we didn’t analyze it objectively enough beforehand, and unfortunately, we took the wrong direction.

Let’s zoom out a bit. Where, in your view, does a developer’s responsibility for a feature’s behavior in production begin and end? And how does that boundary shift as the company grows and the engineering culture matures?

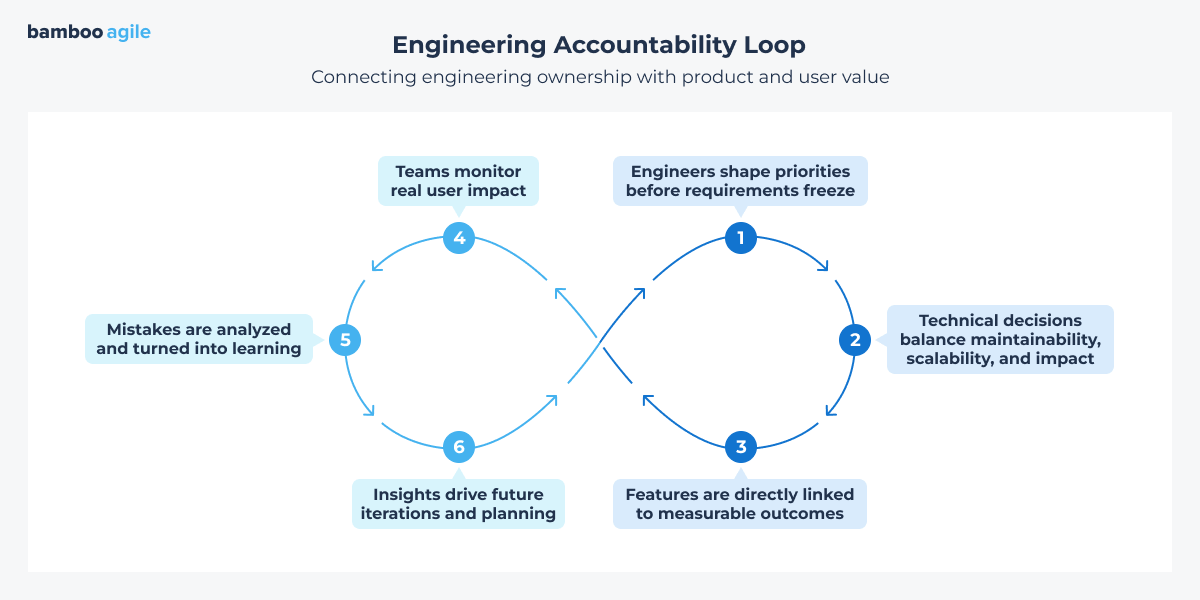

Ideally, responsibility should, to some extent, cover everything. Of course, it’s not just on the developers. One way or another, the whole team shares it – in areas like stability, performance, user value, feedback, efficient use of infrastructure, and so on.

It’s simple: the more deeply people are involved in the overall culture of quality, the more likely the project will succeed at every stage of its life cycle.

Vasilij Ninko

Alexey: I would add that this broader sense of responsibility among developers needs to be encouraged intentionally and from the start. As the company grows, engineers naturally shift their focus from pure technical implementation to areas such as reliability metrics and UX, for example. And it’s important to make clear that this is related to career growth.

How engineering responsibility is built in practice

What should engineers do before coding to make sure a feature is worth building? And at which stages should this happen?

Vasilij: I’d say, ideally, key developers should be involved from the very beginning – when there are no technical requirements yet, just an idea. Say, the team lead. Having a solid understanding of the project’s internal architecture helps him pick the most suitable direction and solution. Knowing the existing tools enables them to move faster by reusing common, well-tested approaches.

Maxim: I agree with Vasilij, but I’d add that this role stays essential at every stage, not just at the beginning. During discovery and requirements analysis, to flag feasibility and challenge assumptions; during prototype and design reviews, to identify hidden costs or complexity early on; during sprint planning, to confirm technical readiness and ensure the success metrics are measurable.

The absence of an “engineering voice” at any of these stages can lead to overspending or even complete project failure.

In your opinion, which practices at the product–engineering interface help engineers ensure their work actually addresses user pain points during development itself? And if you can recall one, please share an example.

Vasilij: I guess the answer is banal – you need to put yourself in the user’s shoes. Not formally, but genuinely feel it: not “how is this implemented in the framework?”, but “does the user actually need this?”. Not “will it be faster to build?”, but “will it run faster for the user?”

At the same time, it’s worth remembering a few basics that some experienced devs might find too obvious to mention in the specs. Say, if there’s a product list, it should be easy to read and properly sorted. If the list has more than ten items, it needs a search bar – especially if the items change frequently. And so on.

Try throttling your own project and simulating a poor connection, then load the solution yourself – on a small screen. If it falls apart, why build it that way in the first place?

The truth is, these pitfalls aren’t always that obvious. Even UI/UX designers fall for them sometimes: they send the components – everything looks great – but once you shrink it to a small screen, everything “breaks.”

Alexey: That’s why, for example, I’d start by putting up a public dashboard showing how features are actually used in production. It makes it clear where to focus, and at the same time, it gives people a sense of pride when they see that the features they built are the most popular. It’s great for motivation.

By the way, I recall that Maxim once suggested the whole team – from engineers to QA – actually use the automotive app they’d built themselves. Every day during their regular commutes. He did the same, too.

Maxim: Yeah, that was the case [smiles]. You wouldn’t believe how many tiny bugs we found – and how many ideas for improvements popped up.

That’s pretty clever. Okay, what other concrete tips can truly motivate developers to think about the long-term success of the part they’re working on? And how can we foster this critical thinking within a project?

Vasilij: I think it’s really important to show developers how their code actually affects other parts of the system and the overall outcome. Let them see real pain points and user feedback – or even join planning and clarification calls when it makes sense.

And, you know, it’s just as essential to highlight their wins – not only to point out mistakes for the sake of lessons learned. Recognition keeps people genuinely motivated to build a better product.

Maxim: …And it’s important to encourage people not to be afraid to think, to ask questions, and to doubt things, I’d add.

And what would you say about common motivation systems in particular?

Alexey: Yes, we often hear about things like OKRs, bonuses for velocity, bug SLAs, and similar tools. In my view, those are more likely to demotivate. And if not, it usually means developers learned to play along with the metrics instead of focusing on tangible outcomes.

I’m more of a believer in keeping things simple – nothing should distract developers from actually building features. The main thing is to provide them as much context as you can and have a straightforward, honest conversation about what’s expected.

Maxim: I wouldn’t entirely agree on that. In my view, OKRs are actually one of the few ways to measure the so-called product mindset – which, essentially, is what we’re talking about right now. It’s pretty hard to measure otherwise.

That said, almost everything depends on how OKRs are applied. For example, a team’s goal might be to improve the user onboarding experience. The key results could be: “increase new user activation rate from 25% to 40%,” “reduce the average time to first value from 5 minutes to 2 minutes,” and “cut support tickets related to onboarding by 20%.”

These kinds of metrics reflect user experience and help developers focus on the work that truly drives user value.

Maxim Leykin

OKR (Objectives and Key Results) is a goal-setting framework developed by Andy Grove at Intel and later popularized by Google. It helps align team goals with the company’s overall strategy. Each Objective is ambitious and measured through specific Key Results, updated regularly. Achieving around 70–80% of them is generally considered a success.

Maxim, let’s clarify this a bit: how should individual developers be evaluated against OKRs, considering it’s mainly a team-level tool? And who should be responsible for setting them?

Maxim: I would say that, depending on the team structure, it can be the Delivery Manager or the Engineering Manager – the person who combines tech expertise with delivery responsibility. Product people can also help define high-level objectives that align with business goals.

But yes, as you rightly noted, OKRs are primarily a team-level tool, so they shouldn’t be directly tied to individual performance reviews. Instead, we can assess each developer’s contribution to the overall team’s key results. In some cases, they can be outstanding even if the overall OKRs weren’t fully met. It also helps to complement OKRs with behavioral metrics such as initiative, communication, mentorship, and problem-solving skills.

Balancing speed, product thinking, and quality

But in practice, when fast delivery is critical, developers often struggle to think deeply and make long-term product decisions. How can we avoid risks in situations where projects are frequently done under deadline pressure?

Vasilij: I’d say – and I think we’d all agree – there’s no foolproof way to avoid that. But if you move in that direction, it’s only logical to make the key architectural and product decisions early on – when the deadlines aren’t that tight yet.

Another good practice, in my opinion, is breaking big tasks down into as many small iterations as possible. It doesn’t solve every problem, but when you get used to finishing and shipping even small things, you sometimes realize the next step isn’t even needed – either because of how the system works or because the client’s priorities have changed.

Basically, if there’s something to deliver – deliver it.

And it is also vital that developers feel secure making thoughtful, product-oriented decisions at every stage. Something that gets rejected in the short term but makes sense for user value in the long run can always be kept for later. All of this only works if the team has good communication.

There’s a lot of debate in the industry about how to balance product and engineering priorities – from Martin Fowler’s First Team idea, with shared ownership and alignment across functions, to Fibery’s approach with separate product and engineering roadmaps but tight coordination. Which model feels closer to you?

Alexey: I’d say a single shared roadmap, but with clearly defined areas of responsibility. And the less micromanagement, the better.

Maxim: I would also recommend leaving a single shared roadmap, but creating special user stories that accumulate tasks like tech debt, code health, innovative frameworks, etc.

We can also try to plan sprints using the “3+1” methodology, where three consecutive sprints are “product outcome” and the 4th sprint is the engineering outcome.

Vasilij: I’d be a bit less categorical here, probably. In my view, all of these approaches can work well, depending on the situation and the team. But what matters more than any “textbook” structure is staying consistent – sticking to the chosen model and keeping decisions aligned over time.

Finally, some say that before QA became a separate role, developers built quality in themselves, or paid later by fixing bugs. Now, it may seem to some that responsibility has weakened, and they argue it should return to developers. What’s your take?

If developers write tests and check how a feature behaves in DEV, UAT, and PROD themselves, no matter what – you should hold on to those people and never let them go [smiles].

Alexey Shinkarev

Maxim: Yes, such developers can be incredibly valuable, but honestly, I’m pretty skeptical about the idea of shifting full responsibility back to them, for three reasons.

First, developers know the code too well and subconsciously avoid edge cases, while QA looks exactly for those failures.

Second, the developer’s mindset is to build, while the tester’s mindset is to break.

And third, there are specific testing practices and tools that no developer has studied.

So I’d say it’s about finding the right balance – where both sides take ownership of quality from their own perspectives, without isolating their function in their own minds.